Open Source Built Technology Stacks

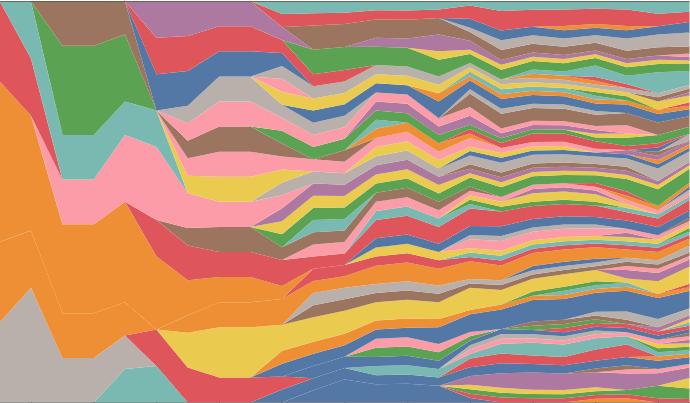

I was engaged in the banal activity of revising my resume, when I innocently created the janky piece of modern art.  It shows the number of technologies I use in my jobs (and would include on my resume), grouped by year. As it clearly shows, the number of technologies started slow, and is now huge. Perhaps the specific tools are no longer important? To explain, let me go back.

It shows the number of technologies I use in my jobs (and would include on my resume), grouped by year. As it clearly shows, the number of technologies started slow, and is now huge. Perhaps the specific tools are no longer important? To explain, let me go back.

My first job tech involved typing code written for an Apple II into a Commodore 64, and in the process making it work. I brought no toolbelt with me, just what I’d learned out of borrowed magazines and from hours of experimentation after school in the back of Mr. McLemore’s class. A few years later, on my first day of the job writing software I received my only tool, a Fortran compiler, and I inserted into my Compaq portable. Two years later, when writing the first technical publishing app for the Macintosh (TechScriber!), we considered buying a text engine, but decided no, and instead, hired Seth and did it ourselves, using just a C compiler and a home-made OO framework. There was no “open source” library to consult. Developers would bring their own set of tricks, or consult books for ideas and algorithms. This meant that progress would be slow, but you (or somebody at the company), knew every line of code.

There was little “free code”, but to speed up development we got more sophisticated tools. Our home-made OO framework helped, and LightspeedC and Pascal gave way to Apple’s MPW, which was a scriptable programming environment, like a configurable Python notebook. I would perform large refactorings by writing a long script with lots of regular expressions that ran overnight; and then if it worked, I’d complete the refactorings in the morning. Then tools like ObjectMaster automatically indexed all my code, foreshadowing tools like 21st century IntelliJ IDEA. These were our trusted steeds. But besides our IDE and a few third party tools, like TMON for debugging, we were on our own.

In the early 1990s, we started having more libraries and frameworks from our compiler suppliers. Apple slowly improved the OS APIs. Then they provided the MacApp framework, LightspeedC included TCL (THINK class library), and then Microsoft offered windowing monoliths. But this is a small list– just a few lines on a Wikipedia page. When Java arrived on the scene, the third party developers got a cohesive library to bootstrap their development.

Once the Internet was going, though, things changed: Open source libraries appeared, and development radically changed. We got competing, easily adoptable tools and code we could adopt, like Apache Log4j, JUnit and the Spring, an open source framework that “disrupted” Sun’s J2EE environment. All of a sudden, we’d pull in libraries and we saw some real reduction in the code we had to write– or improvements in what we could build. And there were a few tools as well; I remember contributing to an open-source source code control tool, MacCVS Pro, providing a visualization of code branches, coordinating awkwardly in, well, CVS.

Finally, Git and Github arrived and the open source world exploded. Free tools, libraries and freemium services became readily available. This meant we also had more code to know. As more software moved to the web, we also got code by calling third part services. This was originally a simple integration, perhaps with a Google Analytics integrations. But these days, it is easy to have a dozen services in use by your web app in the first week of setting things up.

In 1994, it was great to have MacApp on your resume, because it was likely the framework a future employee would use, and you’d spent significant time learning it. But these days, there are so many tools it is hard to know which ones to list. Today’s equivalent of MacApp, React, has a half-dozen tools that go along with it for state management, packaging, deployment, testing, logging, messaging, etc. In that context, having “React” on a resume isn’t saying that much. But to accurately capture the tools, you’d need long lists.

One implication of the current situation is that knowledge of any specific tool is not that important, but what is more important is:

- the ability to evaluate and select tools

- the ability to quickly learn new tools

- knowledge of the overall ecosystem and how tools fit together

- wisdom about the industry that will allow you to properly predict which technologies will see success.

It would be great to include these skills when hiring new engineers. I recently revamped my resume, stripping away the clutter to tell a more coherent story about my career. In the process, as I removed many details from my resume. (I moved them into a spreadsheet.) Seeing it, I couldn’t resist the urge to experiment with visualizing this data. One chart in particular, despite pushing the limits of charting tools and guidelines, vividly illustrates the explosive growth in the number of technologies we developers use day-to-day.

Hover over a color to see a different tool or technology (with some color repeats). Years are along the X axis. Usage is not to any scale. Credit: Technologies I Have Used by NDP

I’ll add some more ideas, and you can poke around in the workbook on observablehq.